Prosecution History:

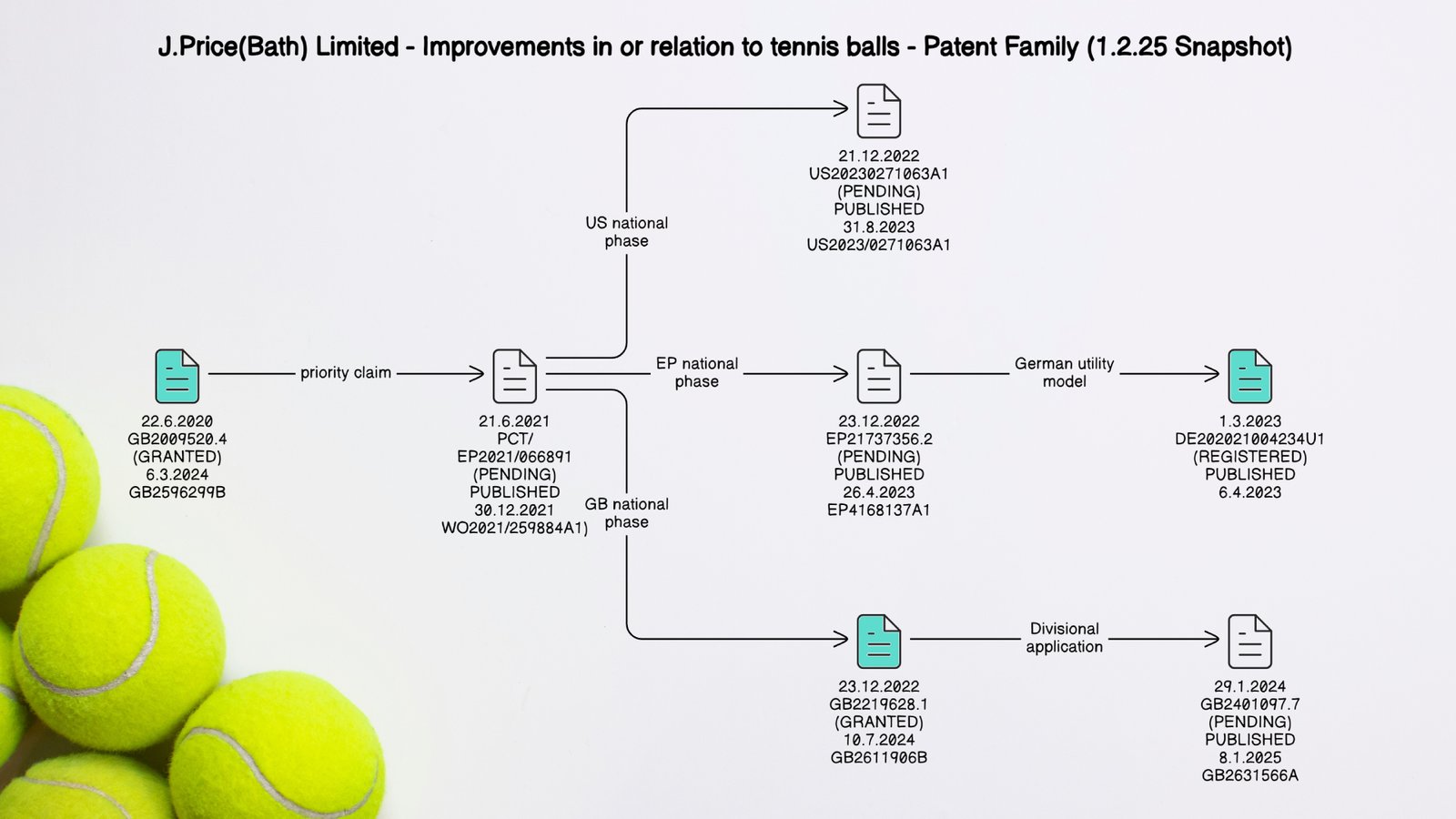

In June 2020, Wiltshire-based J.Price(Bath) Limited based filed UK priority application no. GB2009520.4, and in March 2024, this patent application was granted as publication no. GB2596299B [1].

In June 2021, J.Price(Bath) Limited filed an international application PCT/EP2021/066891 claiming priority from the earlier above-mentioned UK priority application. The international application was published on 30 December 2021 as WO2021/259884A1.

In December 2022, the international application entered into the EP regional phase as well as the US and UK national phases. In March 2023, a German utility model was registered based on the EP national phase application. In July 2024, the UK national phase application was granted as publication no. GB2611906B. In January 2024, divisional application no. GB2401097.7 was filed (from the granted UK national phase patent), and is currently pending.

As depicted in the patent family tree diagram above, the effective priority date of the national phase applications – for the purposes of novelty – is 22 June 2020. This is because the national phase applications are derived from the international application, which claims priority from UK priority application no. GB2009520.4.

In relation to patent term, the national phase applications all have the same filing date i.e., the international filing date of 21 June 2021. Given that a patent usually has a maximum term of 20 years from the filing date, the maximum term of the national phase patents would end in 2041. This represents a potential additional year of protection as compared with the term of the UK priority patent, which would end in 2040. That said, the US and EP national phase applications are currently pending, and not yet granted.

This article aims to briefly summarise the technology disclosed in UK patent GB2596299B of UK priority application no. GB2009520.4 – granted in March 2024 – which formed the original subject-matter for the patent family.

Brief History of Tennis Balls:

Traditionally, tennis balls were either black or white to contrast with the colour of the tennis court. In 1972, the International Tennis Federation (‘ITF’) updated the rules to include yellow tennis balls, as studies in part revealed they were easier for television audiences to see. Did you know Wimbledon initially held onto its classic white balls but eventually made the switch to yellow tennis balls in 1986?

In 1986, the yellow Wimbledon tennis balls made their first appearance, and were highly distinctive; achieved through the use of an exclusive Ultra Vis™ dye and a once-patented process by Slazenger, designed to ensure maximum visibility for both players and spectators.

The shift from traditional white to yellow was based on the human eye’s greater sensitivity to yellow light as compared to white. The Ultra Vis dye produces a specific shade of yellow, with a wavelength between 500 and 560 nm, which creates the vibrant, fluorescent yellow color famously seen on the Wimbledon tennis courts.

Over time, other important characteristics of the tennis ball have evolved:

- the acceptable range for forward and return ball deformations —representing changes in the ball’s diameter under a load of 8.165 kg—reached its current standards in 1996;

- the acceptable mass range of 56.0–59.4 grams for each ball was last updated in 2000, previously set at 56.7–58.5 grams; and

- the acceptable diameter range for a ‘Type 2 ball’ (see Table 1 below), now 6.54–6.86 cm, was last adjusted in 1966 from the earlier measurement of 2.575–2.675 inches [2], although the two ranges are effectively equivalent.

How Tennis Balls are Made: Manufacturing and Standards:

Tennis balls are manufactured to a standard specification as set by the Lawn Tennis Association (‘LTA’) [3] or ITF [4].

According to the ITF, the tennis ball manufacturing procedure includes the following eleven stages [5]:

- Production of Solutions: Rubber is masticated, mixed with powders, soaked in petroleum solvent, and stirred to form a solution of desirable consistency;

- Formulations: Natural rubber is combined with other materials for strength and low gas permeability in precise proportions;

- Extrude: The rubber compound is heated, extruded into rods, cut into pellets, and cooled;

- Form: Pellets are pressed into hemispherical half-shells, partially cured, and trimmed of excess material;

- Edge Buff: Half-shell edges are roughened and coated with adhesive for bonding;

- Cure and Inflate: Half-shells are joined, pressurised using chemicals or compressed air, and vulcanised to form pressurised cores;

- Core Solution: The core is roughened, coated with rubber solution, and tumbled for uniform application;

- Fabric Cover: Cloth is coated with vulcanising solution, cut into blanks, and adhered to the core in two layers;

- Moulding: The ball is heated and pressed to bond the fabric to the core, forming a smooth seam;

- Steaming: Balls are steamed to fluff the cloth, removing any ridges.

- Finishing: Balls are tested, marked with branding, packed in pressurised cans, and dispatched.

According to the ITF, ball approval tests include [6]:

- Pre-compression (and conditioning);

- Mass;

- Size;

- Deformation;

- Rebound; and

- Durability.

According to the ITF, the specifications that a tennis ball must conform to is given in three different types, tabulated below:

| Attribute | Type 1 (Fast) | Type 2 (Medium)* | Type 3 (Slow) |

| Mass (Weight) | 56.0-59.4 grams (1.975-2.095 ounces) | 56.0-59.4 grams (1.975-2.095 ounces) | 56.0-59.4 grams (1.975-2.095 ounces) |

| Size | 6.54-6.86 cm (2.57-2.70 inches) | 6.54-6.86 cm (2.57-2.70 inches) | 7.00-7.30 cm (2.76-2.87 inches) |

| Rebound | 138-151 cm (53-60 inches) | 135-147 cm (53-58 inches) | 135-147 cm (53-58 inches) |

| Forward Deformation | 0.56-0.74 cm (0.220-0.291 inches) | 0.56-0.74 cm (0.220-0.291 inches) | 0.56-0.74 cm (0.220-0.291 inches) |

| Return Deformation | 0.74-1.08 cm (0.291-0.425 inches) | 0.80-1.08 cm (0.315-0.425 inches) | 0.80-1.08 cm (0.315-0.425 inches) |

| Colour | White or yellow | White or yellow | White or yellow |

*This ball may be pressurised or pressureless: the pressureless ball shall have an internal pressure that is no greater than 7 kPa (1 psi).

The Environmental Challenge: Tennis Ball Waste

The physical structure of a tennis ball includes a hollow, two-piece rubber shell, typically filled with air or nitrogen. The shells is coated with a fibrous felt/cloth cover.

It is estimated that each year, approximately 325 million tennis balls are produced, contributing to 20,000 tonnes of waste that is not easily biodegradable.

During recycling, sorting the balls is challenging given that the balls collected vary in terms of types, brands and age. Upon removal of the cloth cover, each ball is likely to exhibit a variation in physical properties and characteristics, potentially due to differences in initial manufacture and subsequent aging and wear.

According to the inventors – in the current state-of-the-art – it has not been possible to recycle used tennis balls into new tennis balls that meet the ITF’s standard specifications.

The Innovation: Recycled Tennis Balls:

GB2596299B [1], titled “Improvements in or relating to tennis balls” claims a tennis ball comprising a hollow core and a fabric cover, the core comprises moulded ball core half shells joined to form a ball, the half shells being formed from a composition comprising a proportion of recycled content and a proportion of unrecycled, new or virgin rubber, in which the recycled content is derived both from tennis ball fibres from the recycled coatings on the recycled tennis balls and recycled rubber from the cores of recycled tennis balls.

Optionally, the patent claims that the tennis ball according to the invention conform to the specifications as outlined in Table 1, above, and briefly discussed hereinbelow. Additionally, the core shell may comprise at least one rubber from the group: natural rubber, polybutadiene, isoprene, styrene-butadiene rubber and mixtures thereof.

The quantity of recycled material in the ball may be in the range 10-75%; 20-75%; or 30-75%. The ball may be a pressurised or pressureless tennis ball.

Modifications to Standard Pressurised Tennis Ball Formulation:

According to the patent disclosure, there are several examples of formulations that may be used to achieve the new tennis balls, made using recycled content from used tennis balls.

The standard tennis ball formulation i.e., prior to the addition of recycled content, is given as follows:

| Component | Parts (pph) |

| Rubber Hydrocarbon Content (RHC) | 100 |

| Natural Rubber | 66 |

| Polybutadiene (synthetic rubber): increases resilience of the formulation | 34 |

| Additives: | |

| Zinc Oxide | 4 |

| Stearic acid | 1 |

| Antioxidant | 1 |

| Clay | 29 |

| Light magnesium carbonate | 38 |

| Sulphur: curative e.g., magnesium sulphate | 3.75 |

| DPG (1,3-diphenylguanadine): middle-speed accelerator | 2.26 |

| CBS (N-Cyclohexyl-2-benzothiazolesulfenamide): vulcanisation accelerator | 2.26 |

| TMTD (Tetramethyl thiuram disulfide): vulcanisation accelerator | 0.25 |

According to the invention, 100pph of recycled content may be added to the base formulation above, so that there is around 1:1 ratio of recycled content and unrecycled content. However, the following additions are also made:

| Additional Additives: | Parts (pph) |

| Sulphur: for reprocessing aged rubber | +1.5 |

| DPG | +1.5 |

| CBS | +1.5 |

| Non staining oil e.g., paraffinic oil: wets the crumbed rubber surface | +3 |

| Keiselguhr: semi reinforcing filler for consistency | +6 |

The inventors used the overall modified formulation to produce recycled tennis balls, moulding half core shells that once combined and covered with cloth, such that the weight percent of recycled content comprised 75 wt.% of the complete ball.

The new tennis balls were tested and the results for each ball were found to be in conformity with ITF standards, including for each ball, the properties: Weight: 58 grams; Deformation: 0.270 inches; and Rebound: 54 inches.

Standard Pressurised Tennis Ball Formulation with 100pph of Recycled Content:

The inventors found that simply combining the standard formulation with 100pph of recycled content produced tennis balls that fell short of the standard specifications in relation to weight and rebound; hence additives were required. That said, the following alterations were made:

- Reversing the ratio pph of Natural Rubber and Polybutadiene from 66:34 to 34:66;

- Adding Keiselghur; and

- Increasing the amounts of curatives.

A novel formulation, as an exemplary embodiment of the invention, is given as follows:

| Component | Parts (pph) |

| Natural Rubber | 34 |

| Polybutadiene (synthetic rubber): increases resilience of the formulation | 66 |

| Additives: | |

| Zinc Oxide | 4 |

| Stearic acid | 1 |

| Antioxidant | 1 |

| Clay | 29 |

| Light magnesium carbonate | 38 |

| Sulphur: curative e.g., magnesium sulphate | 5.25 |

| DPG (1,3-diphenylguanadine): middle-speed accelerator | 3.76 |

| CBS (N-Cyclohexyl-2-benzothiazolesulfenamide): vulcanisation accelerator | 3.76 |

| TMTD (Tetramethylthiuram disulfide): vulcanisation accelerator | 0.25 |

| Recycled tennis ball material | 100 |

| Rubber process oil | 3 |

| Keiselguhr: semi reinforcing filler for consistency | 6 |

Using the above formulation in Table 4, test ball results for each ball were found to be: Weight: 58 grams; Deformation: 0.270 inches; Rebound: 54 inches; and Size: 6.67 cm, which, again, conforms well to the ITF standards, shown in Table 1.

The patent proceeds to give further formulations e.g., where the recycled content is reduced to 50pph and ITF standards are met, as well as for pressureless balls. Read the full patent here [1].

The UK national phase application, granted as publication no. GB2611906B, claims a process of making a hollow rubber tennis ball which incorporates recycled content. Read the full patent here [8].

Conclusion: A Game-Changer for Sustainability:

The patented invention may offer a novel formulation that improves the feasibility of recycling used tennis balls into new ones while adhering to ITF standards. By utilising a substantial proportion of recycled materials, this approach may address challenges related to material variability and manufacturing consistency. It represents a step forward in reducing waste from tennis ball production while maintaining the performance characteristics required for professional and recreational use.

So, the next time you pop open a can of tennis balls, imagine a future where those very balls might one day bounce back into action on a tennis court, rather than ending up in a landfill, as is largely the case at present. It’s a small bounce toward a greener game, and who knows? The love for tennis might soon come with a lighter carbon footprint—game, set, and match for sustainability!

While the dream of truly sustainable tennis balls might still be bouncing on the horizon, there’s plenty we can do in the meantime. Used tennis balls don’t have to go to waste—they can bring joy to dogs, support school sports programs, or find new life in creative projects [9]. If you’re in London (or anywhere in the UK), consider donating your old tennis balls to organizations such as Recycaball, where they’ll be repurposed for good causes. If you’re in the US, RecycleBalls, offer a similar imitative.

For example, Belgian artist – Mathilde Wittock – has been involved in several creative projects that give tennis balls a new life in art, while the projects also raise awareness of the impact of waste [9].

Did you know? Tennis Ball Scent Trade Mark:

Did you know that in 1999, and within the legal framework of the European Union, the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market approved the registration of the “smell of freshly-cut grass” as a trade mark specifically for tennis balls [10]? Stay tuned to The Patent Eye blog for more game-changing innovations in sports and beyond!

References:

[1] UK Granted Patent, GB2596299B – https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/071838339/publication/GB2596299B?q=GB2596299B

[2] History of Tennis Balls – ITF – https://www.itftennis.com/media/2280/balls-history-of-tennis-balls.pdf

[3] LTA Competition Regulations: 5.51-5.52: Tennis Balls – https://www.lta.org.uk/4905d3/siteassets/about-lta/file/lta-competition-regulations-january-2021.pdf

[4] International Tennis Federation: Approved Balls – https://www.itftennis.com/en/about-us/tennis-tech/approved-balls/

[5] Ball Manufacture (ITF) – https://www.itftennis.com/media/2167/balls-ball-manufacture.pdf

[6] Ball Approval Tests (ITF) – https://www.itftennis.com/media/2100/balls-ball-approval-tests.pdf

[7] APPENDIX A : THE RULES OF TENNIS (ITF) – Effective from 1 January 2024 – Appendix 1 – “The Ball” – https://www.itftennis.com/media/12819/2025-itf-ball-approval-procedures.pdf

[8] UK Granted Patent, GB2611906B – https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/071838339/publication/GB2611906B?q=GB2611906B

[9] Giving tennis balls a second life: “Ecological design is circularity” – https://unric.org/en/giving-tennis-balls-a-second-life-ecological-design-is-circularity/

[10] Decision of the Second Appeal Board of 11 February 1999 in Case R 156/1998-2, application No 428.870 – https://www.copat.de/download/R0156_1998-2.pdf

The Patent Eye blog offers a glimpse into the future by showcasing newly granted patents. Join us as we explore the latest innovations shaping our world.

The Patent Eye blog is made available by Alphabet Intellectual Property for informational purposes, in particular, sharing of newly patented technology from granted and published patents available in the public domain. It is not meant to convey legal position on behalf of any client, nor is it intended to convey specific legal advice.

Craving intellectual stimulus? Peer into the insights brought to you by The Patent Eye and explore our latest articles.